The Three Piston Greats-The Last of the Big Propliners

By Bob Allison

By the late fifties, the turboprop revolution had begun. Aircraft like the Vickers Viscount and the Bristol Britannia were quicker than their piston engined contemporaries. Or were they?

The short to medium haul Viscount, flourished. It was dramatically superior to the DC3s, Vikings and Yorks. In 1960 it was Vickers' proud boast that there were always at least four Viscounts airborne somewhere in the world. To complicate the issue, short-haul jets were making their appearance. The French Caravelle and the Russian Tu104 cruised at around 420 knots (kt), somewhat quicker than the Viscount.

The long range Britannia, though, was already threatened with obsolescence by the impending turbojet takeover. Surprisingly, its performance was not significantly superior to the long haul pistons of the day. Although it was a bit quicker than some contemporary pistons, cruising at 310 kt and carried a few more passengers, its range was not significantly better. Nevertheless, it signaled the end of the piston era.

As a young ATC Assistant, I remember being particularly impressed with the big pistons. They were certainly no slouches. These big daddies were pressurised, cruising between flight levels (FL) 210 and 280 (21 000 - 28 000 ft) at around 260 kt. It was their ability to fly high which enabled them to achieve the high true airspeed (TAS) in the cruise. The three main types were the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, Lockheed L1049 Super Constellation and the DC7. Their passenger loads varied with configuration but all were able to carry 80 to 100 passengers.

These were big ships with max takeoff weights (MTOWs) between 55 and 65 tonnes. Needless to say, they needed big power plants to get them off the ground and sustain their high cruising speeds. The Stratocruiser with the highest MTOW at 67 tonnes packed four Pratt and Whitney Wasp Majors of 3500 horsepower (hp) each - 14000 hp in total. Quite some grunt. The Super Connie and the DC7 both used the Wright R3350 of 3250 hp. The quoted cruising speed of the DC7 is 310 kt but I do not recall them flight planning for speeds greater than 290 kt. The Strat and the Super Connie both cruised at 260 kt. Very respectable speeds for piston engined aircraft.

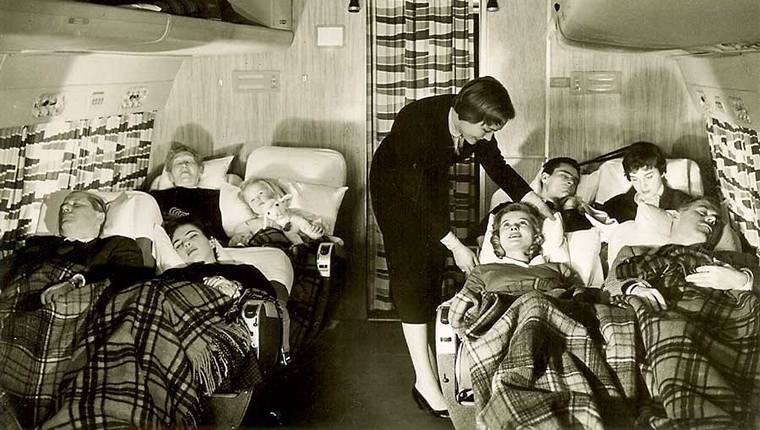

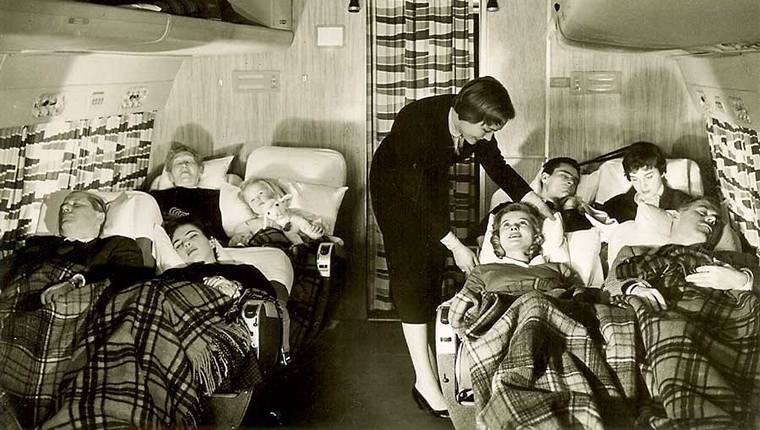

One of the attractions for passengers in these magnificent beasts was the relative luxury in accommodation. Even the economy class was very comfortable. Airlines were, of course, still competing with transatlantic and trans-pacific sea travel with its luxurious accommodation and food. Air travel in that era was not for the working or even middle classes. When the BOAC Monarch Service began in 1949, flying the redoubtable Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, the one-way fares from London to New York were $400 first class and $290 in economy. To put these in perspective, an economy class round trip was six months' pay to a railway booking clerk. So air travel, if not exclusively for the rich and famous, was certainly confined to the well-heeled.

BOAC Stratocruiser in flight. Photo British Airways via Wikipedia

The Strat's double barreled fuselage accommodated 14 passengers (pax) on the lower deck, which could also be configured as a lounge bar. The upper deck seated either 63 or 83 passengers, depending on class configuration. It was also versatile enough to be converted to 28 sleeping berths and four seated passengers. The possible layout, no doubt used by some airlines such as Pan American, allowed up to 100 seats on the upper deck plus the 14 downstairs. It could thus pack in eight more than the Super Connie and 10 more than the DC7. Significant? I'm not sure. Especially as its slightly smaller rivals could both outrange the Strat by 1000 nautical miles. The Boeing was also more expensive to buy and operate. Boeing built 56 of these aircraft, including the prototype, operated by 10 airlines from six countries.

Stratocruiser interior

The Stratocruiser, though, was an ungainly aircraft. An account of flying the aircraft by BOAC captain, Tony Spooner DSO, DFC, gives the impression it was a bit of a fistfull to fly. Boeing was not keen on hydraulics in the days before non-flammable hydraulic fluids, so most of the aircraft's systems were electric. Even the landing gear was electrically operated. The enormous 28 cylinder Wasp Major engines were somewhat temperamental. Tony Spooner recalls, 'Generally the engines were a troublesome feature, and we all chalked up a large number of three-engined hours. I suppose that I must have had about 100 at least in the 4,500hr in which I flew this strange aircraft. However, I never had to struggle home on only two engines, as some of my fellow captains had to.' Landings and take offs were also rather interesting, 'The robustness of the nosewheel leg was proved on almost every landing, as the Strat, when near the ground, had a mind of its own and we used to arrive (one did not land a Strat; one arrived) with the most appalling thumps. No amount of heaving back on the pole would induce the main wheels to make contact first'. On take off, 'The aircraft also ran on its nosewheel alone for several hundred yards, …quite exciting in a strong crosswind. The huge tail made the aircraft try to weathercock'.

Stratocruiser Cockpit

Another disconcerting feature of the Strat was its propensity for over speeding propellers. On Tony's first Strat trip in command, he says, 'Almost as soon as the wheels had left the ground after my first ever maximum-weight take-off, from Keflavik Airport, Iceland, on a vile and stormy night, I experienced a run-away propeller'. Fortunately his simulator training enabled him to deal with the emergency and land safely.

Tony was lucky, though. Of the 55 Strats in airline service, 13 were lost in various accidents the majority due to overspending propellers. This often ripped the entire engine mounting from the wing. A number of over speeding propeller incidents had less disastrous consequences when skillful crews were able to land or ditch the aircraft with minimal loss of life.

The Strat's range was something of a drawback, too. It could not make London to New York direct, often needing three refuelling stops in adverse winds. It was quite usual for a flight to stop in Prestwick, Keflavik and Gander. Thus it could often take as much as 16 or more hours to reach the States.

Lockheed Super Constellation. Photo © Jon Proctor/commons.wikimedia.org

The Lockeed 1049G Super Constellation was held in much greater regard by its crews. The original Constellation design was in response to a specification issued by the iconic Howard Hughes for TWA. The Super Connie first flew in 1951. The L-1049C could get off the ground at just under 54 and a half tonnes, carrying up to 106 pax with enough fuel for almost 4500 nautical miles (nm). As with the Strat, DC6 and DC7, it was pressurised, usually cruising at between FL180 and FL240, though getting there took quite a while. The Super Connie could trundle along quite happily at 260 kt. Eminently respectable when you consider its piston power. The Wright R3350 engines produced 3250 hp each, totalling 13000 hp.

Constellation cockpit

Constellation interior

All this made the Super Constellation quite popular with the airlines. When Howard Hughes placed his initial order for Constellations with Lockheed, he stipulated that no other airline should be supplied with the aircraft until all his had been delivered. In all, 259 civil L1049s were built and sold to over 15 airlines in 10 countries, including SAA, Trek Airways and Luxavia. Without doubt, the L-1049 Super Constellation and its big sister the L1649 Starliner, were by far the best looking and most evocative of all the big pistons.

A Delta Airlines Douglas DC-7 over the Coast. Photo commons.wikimedia.org

Nevertheless, the DC7 has to take first place among the big pistons. A development of the DC6, an early post-war pressurised airliner, the DC7's performance was way ahead of the others in speed, range and airline popularity. Douglas sold 343 DC7s to 23 airlines from 15 countries, again including SAA with the C variant. This was dubbed the 'Seven Seas' by some of its operators.

DC-7 Cockpit

DC-7 Interior

With a 7 ft longer fuselage and 10 ft greater wingspan than its predecessor, Douglas designers were able to increase the DC7's performance dramatically. The Wright R-3350 radials developing 3400 hp each helped it carry 16 more passengers nearly 40 kt faster and 1500 nm further, than the DC6B. In common with the other big pistons of the day, it cruised at up to FL280. All this helped Douglas to sell 343 of them in its five year production run between 1953 and 1958.

The birth of the long range jet-liner brought to a close the magic of the piston era. No longer would air travellers fell just a little superior to their fellows. Mass air transport had begun, leaving a little sadness in the hearts of the more wistful aviators.

The short to medium haul Viscount, flourished. It was dramatically superior to the DC3s, Vikings and Yorks. In 1960 it was Vickers' proud boast that there were always at least four Viscounts airborne somewhere in the world. To complicate the issue, short-haul jets were making their appearance. The French Caravelle and the Russian Tu104 cruised at around 420 knots (kt), somewhat quicker than the Viscount.

The long range Britannia, though, was already threatened with obsolescence by the impending turbojet takeover. Surprisingly, its performance was not significantly superior to the long haul pistons of the day. Although it was a bit quicker than some contemporary pistons, cruising at 310 kt and carried a few more passengers, its range was not significantly better. Nevertheless, it signaled the end of the piston era.

As a young ATC Assistant, I remember being particularly impressed with the big pistons. They were certainly no slouches. These big daddies were pressurised, cruising between flight levels (FL) 210 and 280 (21 000 - 28 000 ft) at around 260 kt. It was their ability to fly high which enabled them to achieve the high true airspeed (TAS) in the cruise. The three main types were the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, Lockheed L1049 Super Constellation and the DC7. Their passenger loads varied with configuration but all were able to carry 80 to 100 passengers.

These were big ships with max takeoff weights (MTOWs) between 55 and 65 tonnes. Needless to say, they needed big power plants to get them off the ground and sustain their high cruising speeds. The Stratocruiser with the highest MTOW at 67 tonnes packed four Pratt and Whitney Wasp Majors of 3500 horsepower (hp) each - 14000 hp in total. Quite some grunt. The Super Connie and the DC7 both used the Wright R3350 of 3250 hp. The quoted cruising speed of the DC7 is 310 kt but I do not recall them flight planning for speeds greater than 290 kt. The Strat and the Super Connie both cruised at 260 kt. Very respectable speeds for piston engined aircraft.

One of the attractions for passengers in these magnificent beasts was the relative luxury in accommodation. Even the economy class was very comfortable. Airlines were, of course, still competing with transatlantic and trans-pacific sea travel with its luxurious accommodation and food. Air travel in that era was not for the working or even middle classes. When the BOAC Monarch Service began in 1949, flying the redoubtable Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, the one-way fares from London to New York were $400 first class and $290 in economy. To put these in perspective, an economy class round trip was six months' pay to a railway booking clerk. So air travel, if not exclusively for the rich and famous, was certainly confined to the well-heeled.

BOAC Stratocruiser in flight. Photo British Airways via Wikipedia

The Strat's double barreled fuselage accommodated 14 passengers (pax) on the lower deck, which could also be configured as a lounge bar. The upper deck seated either 63 or 83 passengers, depending on class configuration. It was also versatile enough to be converted to 28 sleeping berths and four seated passengers. The possible layout, no doubt used by some airlines such as Pan American, allowed up to 100 seats on the upper deck plus the 14 downstairs. It could thus pack in eight more than the Super Connie and 10 more than the DC7. Significant? I'm not sure. Especially as its slightly smaller rivals could both outrange the Strat by 1000 nautical miles. The Boeing was also more expensive to buy and operate. Boeing built 56 of these aircraft, including the prototype, operated by 10 airlines from six countries.

Stratocruiser interior

The Stratocruiser, though, was an ungainly aircraft. An account of flying the aircraft by BOAC captain, Tony Spooner DSO, DFC, gives the impression it was a bit of a fistfull to fly. Boeing was not keen on hydraulics in the days before non-flammable hydraulic fluids, so most of the aircraft's systems were electric. Even the landing gear was electrically operated. The enormous 28 cylinder Wasp Major engines were somewhat temperamental. Tony Spooner recalls, 'Generally the engines were a troublesome feature, and we all chalked up a large number of three-engined hours. I suppose that I must have had about 100 at least in the 4,500hr in which I flew this strange aircraft. However, I never had to struggle home on only two engines, as some of my fellow captains had to.' Landings and take offs were also rather interesting, 'The robustness of the nosewheel leg was proved on almost every landing, as the Strat, when near the ground, had a mind of its own and we used to arrive (one did not land a Strat; one arrived) with the most appalling thumps. No amount of heaving back on the pole would induce the main wheels to make contact first'. On take off, 'The aircraft also ran on its nosewheel alone for several hundred yards, …quite exciting in a strong crosswind. The huge tail made the aircraft try to weathercock'.

Stratocruiser Cockpit

Another disconcerting feature of the Strat was its propensity for over speeding propellers. On Tony's first Strat trip in command, he says, 'Almost as soon as the wheels had left the ground after my first ever maximum-weight take-off, from Keflavik Airport, Iceland, on a vile and stormy night, I experienced a run-away propeller'. Fortunately his simulator training enabled him to deal with the emergency and land safely.

Tony was lucky, though. Of the 55 Strats in airline service, 13 were lost in various accidents the majority due to overspending propellers. This often ripped the entire engine mounting from the wing. A number of over speeding propeller incidents had less disastrous consequences when skillful crews were able to land or ditch the aircraft with minimal loss of life.

The Strat's range was something of a drawback, too. It could not make London to New York direct, often needing three refuelling stops in adverse winds. It was quite usual for a flight to stop in Prestwick, Keflavik and Gander. Thus it could often take as much as 16 or more hours to reach the States.

Lockheed Super Constellation. Photo © Jon Proctor/commons.wikimedia.org

The Lockeed 1049G Super Constellation was held in much greater regard by its crews. The original Constellation design was in response to a specification issued by the iconic Howard Hughes for TWA. The Super Connie first flew in 1951. The L-1049C could get off the ground at just under 54 and a half tonnes, carrying up to 106 pax with enough fuel for almost 4500 nautical miles (nm). As with the Strat, DC6 and DC7, it was pressurised, usually cruising at between FL180 and FL240, though getting there took quite a while. The Super Connie could trundle along quite happily at 260 kt. Eminently respectable when you consider its piston power. The Wright R3350 engines produced 3250 hp each, totalling 13000 hp.

Constellation cockpit

Constellation interior

All this made the Super Constellation quite popular with the airlines. When Howard Hughes placed his initial order for Constellations with Lockheed, he stipulated that no other airline should be supplied with the aircraft until all his had been delivered. In all, 259 civil L1049s were built and sold to over 15 airlines in 10 countries, including SAA, Trek Airways and Luxavia. Without doubt, the L-1049 Super Constellation and its big sister the L1649 Starliner, were by far the best looking and most evocative of all the big pistons.

A Delta Airlines Douglas DC-7 over the Coast. Photo commons.wikimedia.org

Nevertheless, the DC7 has to take first place among the big pistons. A development of the DC6, an early post-war pressurised airliner, the DC7's performance was way ahead of the others in speed, range and airline popularity. Douglas sold 343 DC7s to 23 airlines from 15 countries, again including SAA with the C variant. This was dubbed the 'Seven Seas' by some of its operators.

DC-7 Cockpit

DC-7 Interior

With a 7 ft longer fuselage and 10 ft greater wingspan than its predecessor, Douglas designers were able to increase the DC7's performance dramatically. The Wright R-3350 radials developing 3400 hp each helped it carry 16 more passengers nearly 40 kt faster and 1500 nm further, than the DC6B. In common with the other big pistons of the day, it cruised at up to FL280. All this helped Douglas to sell 343 of them in its five year production run between 1953 and 1958.

The birth of the long range jet-liner brought to a close the magic of the piston era. No longer would air travellers fell just a little superior to their fellows. Mass air transport had begun, leaving a little sadness in the hearts of the more wistful aviators.

|

|

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.