Adrienne Bolland - 212 Loops in one Hour

By Willie Bodenstein

Born into a large family outside Paris, she became a pilot in her twenties to pay off gambling debts. Bolland went to Caudron's headquarters at Le Crotoy, on the English Channel in northern France, and signed up for flying lessons. A typographical error added the second "l" to her name, which she kept for the rest of her life. She earned her pilot's license in two months. While her instructors saw great potential as a pilot, on the ground she continued to be difficult to get along with, sometimes physically attacking those she disagreed with. She was often grounded for disciplinary reasons. "I became a different person in an airplane. I felt small, humble," she said later.

Caudron then asked her to go to Argentina to do demonstration flights. After she arrived she began planning her Andes flight. The G3s that had been sent along to Argentina with her had been designed for use as military observation aircraft during World War I. Fragile and powered by Le Rhône 80 hp engines it was not ideal for the trip. With only 40 hours of flight time and neither maps nor any knowledge of the area she took off from Mendoza on 1 April 1921.

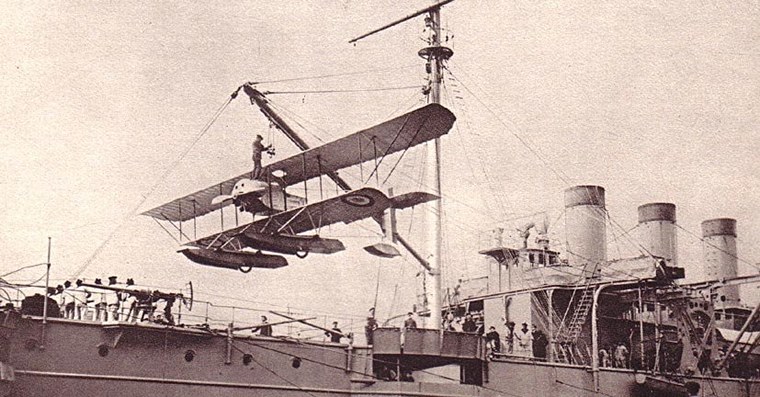

Caudron seaplane, being hoisted onboard La Foudre in April 1914.Photo commons.wikimedia.org

Pilots had been attempting to cross the Andes since 1913, and the National Congress of Chile had offered a prize of 50,000 pesos for the first successful crossing of the range by a Chilean (if no foreigner had done so first) between the 31st and 35th parallels, where the highest peaks lay. Chilean Army officer Dagoberto Godoy claimed the prize in 1918.

Andes in the area of Bolland's flight, seen from a commercial flight in 2008. Photo Jorge Morales Piderit/commons.wikimedia.org

Bolland's flight was especially challenging. The G.3 could not fly much higher than 4,500 metres (14,800 ft), well below the range's summits, which reach up to 6,959 metres (22,831 ft) at Aconcagua, South America's highest peak. So, she had to fly between and around them and through valleys, a riskier route than Godoy and her predecessors had chosen. The flight suit and pyjamas she wore under her leather jacket were stuffed with newspapers, which proved incapable of keeping her warm. The plane had no windshield, and the blood vessels in her lips and nose burst from the cold air at that altitude during the four-hour flight.

Caudron. Photo L. G Trapp / Airspace Museum / commons.wikimedia.org

She eventually landed in Santiago, the capital, exhausted and almost frozen to death. Many people had gathered to celebrate the feat. The French consul, who had believed it was an April Fool's Day joke, was not among them.

Bolland's accomplishment went largely unnoticed in her homeland at the time. In 1924, she was created a Knight of the Legion of Honour in belated recognition of her Andes flight. She continued to fly, setting a women's record of 212 loops on 27 May 1924.

In addition to the awards she received throughout her lifetime, she has been recognized more recently. A street and lycée have been named for her in Poissy, another Paris suburb. In 2005 La Poste, the French postal service, issued a stamp honouring her. The new Paris Tramway have named nine of the 26 stops after notable women, and on the boulevard Mortier in the 20th arrondissement there is one named in her honour. She died in Paris in 1975.

|

|

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.