World War Two

Aviators and Aircraft during WW1

In World War I the fighter reigned supreme. It was the prime killing machine in the air. That changed in WWII. The role of the fighter, especially in the later days of the war, changed to a device to protect the thousands of bombers that did the killing. Dogfights still happened. In WWII pilots still became Aces but conspicuous bravery was no longer enough to be awarded a VC, only a daring or pre-eminent act of valour or self-sacrifice, or extreme devotion to duty in the face of the enemy would suffice and the crews of the bombers did so in large numbers.

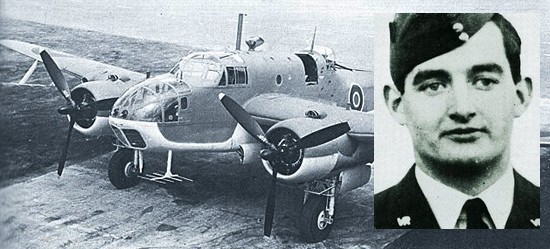

Donald Edward Garland & Thomas Gray / Fairy Battle. Photo commons.wikimedia.org. Donald Edward Garland was 21 years old and a Flying Officer in No. 12 Squadron when on 12 May 1940 together with 25 year old sergeant Thomas Gray in formation with five other Fairy Battles were tasked to demolish a vital that were being used by the invading army. Flying Officer Garland was leading the attack. All the aircrews of the squadron concerned volunteered for the operation. Orders were issued that the attack was to be delivered at low altitude and the bridge was to be destroyed at all costs. As had been expected, exceptionally intense machine-gun and anti-aircraft fire was encountered. Moreover, the bridge area was heavily protected by enemy fighters. In spite of this, the formation successfully delivered a dive-bombing attack from the lowest practicable altitude. British fighters in the vicinity reported that the target was obscured by the bombs bursting on it and near it. Only one of the five aircraft concerned returned from this mission. The pilot of this aircraft reports that besides being subjected to extremely heavy anti-aircraft fire, through which they dived to attack the objective, their aircraft was also attacked by a large number of enemy fighters after they had released their bombs on the target. Much of the success of this vital operation must be attributed to the formation leader, Flying Officer Garland, and to the coolness and resource of Sergeant Gray, who in most difficult conditions navigated Flying Officer Garland's aircraft in such a manner that the whole formation was able successfully to attack the target in spite of subsequent heavy losses. Flying Officer Garland and Sergeant Gray did not return. They were both awarded the VC in a joint citation.

Kenneth Campbell / Beaufort Bristol. Photo wikimedia.org. Scotsman Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell VC (21 April 1917 - 6 April 1941) was mobilised for RAF service in September 1940 as a in the Bristol Beaufort torpedo bomber. He later joined No. 22 Squadron RAF in September 1940 and in March 1941 torpedoed a merchant vessel near Borkum. A few days later, whilst on a sortie, he was set upon by pair of Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters but managed to escape. On 6 April 1941 over Brest Harbour, France, Flying Officer Campbell attacked the German battleship Gneisenau. The Gneisenau was secured alongside the wall on the north shore of the harbour, protected by a stone mole bending around it from the west whilst on rising ground behind the ship stood protective batteries of guns. Other batteries were clustered thickly round the two arms of land which encircle the outer harbour. In this outer harbour near the mole were moored three heavily armed anti-aircraft ships, guarding the battle cruiser. Even if an aircraft succeeded in penetrating these formidable defences, it would be almost impossible, after delivering a low-level attack, to avoid crashing into the rising ground beyond. He flew his Beaufort through the gauntlet of concentrated anti-aircraft fire from about 1000 weapons of all calibres and launched a torpedo at a height of 50 feet (15 m). The battle cruiser was severely damaged below the water-line and was obliged to return to the dock whence she had come only the day before. Generally, once a torpedo was dropped, an escape was made by low-level jinking at full throttle. Because of rising ground surrounding the harbour, Campbell was forced into a steep banking turn, revealing the Beaufort's full silhouette to the gunners. The aircraft met a withering wall of flak and crashed into the harbour. Campbell did not return and he was awarded the VC posthumously.

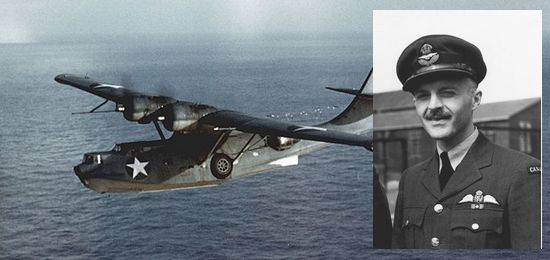

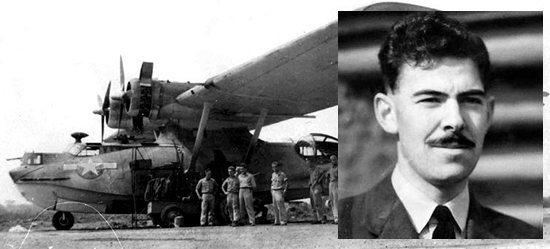

David Ernest Hornell / Catalina. Photo U.S. Navy Naval History and Heritage Command/ commons.wikimedia.org. Canadian David Ernest Hornell VC (26 January 1910 - 24 June 1944) enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in January 1941 and received his pilot's wings in September the same year. On 24 June 1944 Flight Lieutenant Hornell was flying as aircraft captain on a Consolidated Canso[Catalina] amphibian aircraft from RAF Wick in Northern Scotland, on anti-submarine patrol in the North Atlantic. The patrol had lasted for some hours when a fully-surfaced U-boat was sighted. Hornell at once turned to the attack. The U-boat altered course and opened up with anti-aircraft fire which became increasingly fierce and accurate. At a range of 1,200 yards, the front guns of the aircraft replied; then its starboard guns jammed, leaving only one gun effective. Hits were obtained on and around the conning-tower of the U-boat, but the aircraft was itself hit, two large holes appearing in the starboard wing. Ignoring the enemy's fire, Hornell carefully manoeuvred for the attack. Oil was pouring from his starboard engine, which was, by this time, on fire, as was the starboard wing. The aircraft was hit again and again by the U-boat's guns. Holed in many places, it was vibrating violently and very difficult to control. Nevertheless, the Hornell decided to press home his attack. He brought his aircraft down very low and released his depth charges in a perfect straddle. The bows of the U-boat were lifted out of the water; it sank and the crew were seen in the sea. Hornell contrived, by superhuman efforts at the controls, to gain a little height. The fire in the starboard wing had grown more intense and the burning engine fell off. The plight of aircraft and crew was now desperate. With the utmost coolness, the Hornell took his aircraft into wind and brought it safely down on the heavy swell. Badly damaged and blazing furiously, the aircraft rapidly settled. There was only one serviceable dinghy and this could not hold all the crew. So they took turns in the water, holding on to the sides. Two of the crew succumbed from exposure. An airborne lifeboat was dropped to them but fell some 500 yards down wind. The men struggled vainly to reach it and Flight Lieutenant Hornell, who throughout had encouraged them by his cheerfulness and inspiring leadership, proposed to swim to it, though he was nearly exhausted. He was with difficulty restrained. The survivors were finally rescued after they had been in the water for 21 hours. By this time Flight Lieutenant Hornell was blinded and completely exhausted. He died shortly after being picked up.

John Alexander Cruickshank /Catalina. Photo commons.wikimedia.org. Scotsman John Alexander Cruickshank VC (born 20 May 1920) was twenty-four years old when he piloted a Consolidated Catalina anti-submarine flying boat from Sullom Voe on 17 July 1944 on a patrol north into the Norwegian Sea.There the "Cat" found a German U-boat on the surface. At this point in the war U-boats were fitted with anti-aircraft guns and Cruickshank had to fly the Catalina into the hail of flak put up by the U-boat. On that first pass his depth charges did not release. Despite the flack he brought the aircraft back round for a second pass and this time straddled the U-boat with his charges sinking it with all 52 crewmembers. The German flak however had been deadly accurate, killing the Catalina's navigator and injuring four crewmen, including the second pilot Flight Sergeant Jack Garnett and Cruickshank himself. Cruickshank had been hit in seventy-two places, with two serious wounds to his lungs and ten penetrating wounds to his lower limbs. Despite this he refused medical attention until he was sure that the appropriate radio signals had been sent and the aircraft was on course for its home base. Even then he refused morphine, aware that it would cloud his judgement. Flying through the night it took the damaged Catalina five and a half hours to return to Sullom Voe with the injured Garnett at the controls and Cruickshank lapsing in and out of consciousness in the back. Once there Cruickshank returned to the cockpit and took command of the aircraft again. Deciding that the light and the sea conditions for a water landing were too risky for the inexperienced Garnett to put the aircraft down safely, he kept the flying boat in the air circling for an extra hour until he considered it safer, when they landed the Catalina on the water and taxied to an area where it could be safely beached. When the RAF medical officer boarded the aircraft he had to give Cruickshank a blood transfusion before he was considered stable enough to be transferred to hospital. John Cruickshank's injuries were such that he never flew in command of an aircraft again and after the war he returned to his pre-war job of banking. For his actions in sinking the U-Boat and saving his crew he received the Victoria Cross while Flight Sergeant Jack Garnett received the Distinguished Flying Medal.

Robert Hampton Gray / Vought Corsair. Photo USN/commons.wikimedia.org. Robert Hampton "Hammy" Gray VC, DSC (November 2, 1917 - August 9, 1945) was a Canadian naval officer and pilot. In 1940, following education at the University of Alberta and University of British Columbia he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve. Originally sent to England for training, Gray was sent back to Canada to train at RCAF Station Kingston where he qualified as a pilot for the British Fleet Air Arm in September 1941. Gray was first assigned to the African theatre where he spent two years flying Hawker Hurricanes. He then trained to fly the Corsair fighter and in 1944 was assigned to 1841 Squadron, based on HMS Formidable. In August 1944, he took part in a series of unsuccessful raids against the German battleship Tirpitz, in Norway. On August 29, 1944, he was Mentioned in Despatches for his participation in an attack on three German destroyers, during which his plane's rudder was shot off. On January 16, 1945, he received a further Mention, "For undaunted courage, skill and determination in carrying out daring attacks on the German battleship Tirpitz. On August 9, 1945, at Onagawa Bay, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray, flying an Vought F4U Corsair, led an attack on a group of Japanese naval vessels. Gray targeted the Etorofu-class escort ship Amakusa. In the face of fire from shore batteries and a heavy concentration of fire from some five warships Lieutenant Gray pressed home his attack, flying very low in order to ensure success, and, although he was hit and his aircraft was in flames, he obtained at least one direct hit, sinking the destroyer. Lieutenant Gray has consistently shown a brilliant fighting spirit and most inspiring leadership. Gray was one of the last Canadians to die during World War II, and was the last Canadian to be awarded the Victoria Cross and was one of only one of only two members of the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm to have been awarded the Victoria Cross during the war.

David Samuel Anthony Lord Douglas Dakota. Photo commons.wikimedia.org. Irishman David Samuel Anthony Lord VC, DFC (18 October 1913 - 19 September 1944) enlisted in the RAF in 1936. He underwent pilot training, becoming a Sergeant Pilot in 1939 with No. 31 Squadron RAF on the North West Frontier, flying the Vickers Valentia biplane. In 1941 No. 31 squadron was the first unit to receive the Douglas DC-2 which was followed by both the Douglas DC-3 and C47. He flew in the Middle East, (being injured in a crash) before being posted back to India. Commissioned in 1942, he flew on supply missions over Burma. On 19 September 1944 during the Battle of Arnhem in the Netherlands, the British 1st Airborne Division was in desperate need of supplies. Flight Lieutenant Lord, flying Dakota III through intense enemy anti-aircraft fire was twice hit and had one engine burning. He managed to drop his supplies, but at the end of the run found that there were two containers remaining. Although he knew that one of his wings might collapse at any moment he nevertheless made a second run to drop the last supplies and then ordered his crew to bail out. A few seconds later the Dakota crashed in flames with its pilot and six crew, only the navigator, F/Lt Harold King survived, becoming a prisoner of war. It was only on his release in mid-1945 that the story of Lord's action was known, and David Lord was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Pilot Officer C Barton /Handley Page Halifax. Photo commons.wikimedia.org. Englishman Cyril Joe Barton VC (5 June 1921 - 31 March 1944) volunteered for aircrew duties and joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on 16 April 1941. After pilot training via the Arnold Scheme at Maxwell Fieldand 'Darr Aero Tech' in the United States of America. He qualified as a Sergeant Pilot on 10 November 1942 and then returned to England and completed his training with No. 1663 Heavy Conversion Unit at Rufforth, Yorkshire. On 5 September 1943, Barton and his crew joined No.78 Squadron, and Barton was commissioned as a Pilot Officer three weeks later. Their first first operational mission was against a target at Montlucon in occupied France. Barton completed nine sorties with No.78 until 15 January 1944, when he was posted to No.578 Squadron. His second sortie with the new Squadron was an attack upon the city of Stuttgart in Germany, flying in Halifax LK797 (codename LK-E). By 30 March 1944, he had completed six sorties in LK797, which the crew had named Excalibur. Prior to his final mission from RAF Burn, Barton had already taken part in four attacks upon Berlin. On the night of 30 March 1944, while flying in an attack on the city of Nuremberg, in Germany, whilst 70 miles (110 km) from the target, Pilot Officer Barton's Handley Page Halifax bomber (LK797) was badly shot-up in attacks by a Junkers Ju 88 and a Messerschmitt 210, resulting in two of its fuel tanks being punctured, both its radio and rear turret gun port being disabled, the starboard inner engine being critically damaged and the internal intercom lines being cut. In a running battle, despite the attacks, Barton escaped his faster and more agile assailants. However, a misunderstanding in on-board communications in the aircraft at the height of the crisis resulted in three of the 7-man crew bailing out, leaving Barton with no navigator, bombardier or wireless operator. Rather than turn back for England, he decided to press on with the mission deep into the Reich's heartland. Arriving over the target, he released the bomb payload himself and then, as Barton turned the aircraft for home, its ailing starboard engine blew-up. He nursed the damaged airframe over a four-and-a-half hour flight with no navigational assistance back across the hostile defences of Germany and occupied Europe, and across the North Sea. As LK797 crossed the English coast at dawn 90 miles to the north of its base its fuel ran out because of the battle damage leakage and, with only one engine still running on vapours, and at too low a height to allow a remaining crew bail-out by parachute, Barton crash-landed the bomber at the village of Ryhope, steering away in the final descent from the houses and coal pit-head workings. Barton was pulled from the wrecked aircraft alive but died of injuries sustained in the landing before he reached the hospital. The three remaining on-board members of the crew survived the forced landing. One local man, a miner, also died when he was struck by a part of the aeroplane's wreckage during the impact of the crash. Barton was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously for his actions.

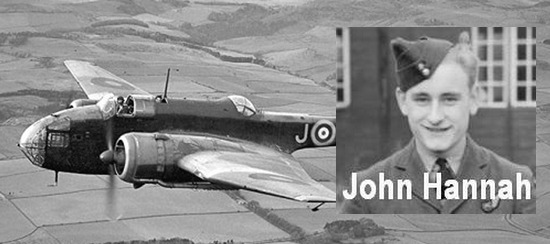

Roderick Alastair Brook Learoyd / Handley Page Hampden. Photo Imperial War Museum. Englishman Roderick Alastair Brook Learoyd VC (5 February 1913 - 24 January 1996) joined the RAF in March 1936. He took a short service commission as an acting pilot officer on 18 May 1936 and He was posted to 49 Squadron, Bomber Command equipped with Hawker Hinds. In March 1938, 49 Squadron moved to Scampton and became the first RAF squadron to re-equip with the new Handley Page Hampden bomber. Learoyd was promoted to flying officer on 23 December 1938. On 12 August 1940 eleven Hampdens , six from 49 Squadron, five from 83 Squadron, were detailed to destroy the old aqueduct carrying the canal over the river Ems, north of Münster. Flight Lieutenant Learoyd was one of the pilots briefed to bomb. Learoyd was detailed as pilot of Hampden P4403, "EA-M", and his crew comprised Pilot Officer John Lewis (Observer), Sergeant Walter Ellis (wireless operator-gunner) and LAC William Rich (ventral gunner). Of the other Hampdens which made the attack that night, two were destroyed and two more were badly hit. Flight Lieutenant Learoyd took his plane into the target at only 150 feet, in the full glare of the searchlights and flak barrage all round him. After commencing its bombing run Learoyd's aircraft was badly damaged, including a ruptured hydraulic system, resulting in inoperable wing flaps and a useless undercarriage. Wing damage, though serious, had fortunately missed the wing petrol tanks. Despite this damage the bombs were duly dropped and Learoyd managed to get his crippled plane back to England where he decided that a night landing would be too dangerous for his crippled aircraft and so circled base until first light, finally safely landing without causing injury to his crew or further damage to his aircraft. Learoyd was awarded the Victoria Cross for his action.

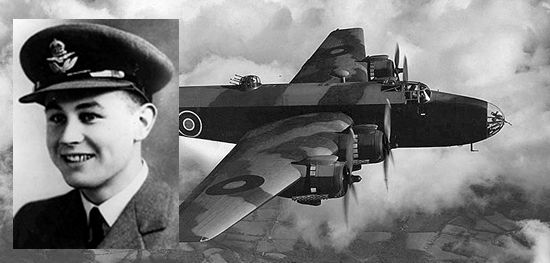

John Hannah / Handley Page Hamden. Photo Imperial War Museum. Scotsman John Hannah VC (27 November 1921 - 7 June 1947) joined the Royal Air Force in 1939 as a wireless operator. He was promoted to sergeant in 1940 and was attached to No. 83 Squadron, flying Handley Page Hampden bombers as a wireless operator/gunner. On the night of 15th September, 1940, Sergeant Hannah was the wireless operator/air gunner in an aircraft engaged in a successful attack on an enemy barge concentration at Antwerp. It was then subjected to intense anti-aircraft fire and received a direct hit from a projectile of an explosive and incendiary nature, which apparently burst inside the bomb compartment. A fire started which quickly enveloped the wireless operators and rear gunners' cockpits, and as both the port and starboard petrol tanks had been pierced, there was grave risk of the fire spreading. Sergeant Hannah forced his way through to obtain two extinguishers and discovered that the rear gunner had had to leave the aircraft. He could have acted likewise, through the bottom escape hatch or forward through the navigators hatch, but remained and fought the fire for ten minutes with the extinguishers, beating the flames with his log book when these were empty. During this time thousands of rounds of ammunition exploded in all directions and he was almost blinded by the intense heat and fumes, but had the presence of mind to obtain relief by turning on his oxygen supply. Air admitted through the large holes caused by the projectile made the bomb compartment an inferno and all the aluminium sheet metal on the floor of this airman's cockpit was melted away, leaving only the cross bearers. Working under these conditions, which caused burns to his face and eyes, Sergeant Hannah succeeded in extinguishing the fire. He then crawled forward, ascertained that the navigator had left the aircraft, and passed the latter's log and maps to the pilot. Hannah was 18 years old, making him the youngest recipient of the Victoria Cross for aerial operations (and the youngest for World War II).

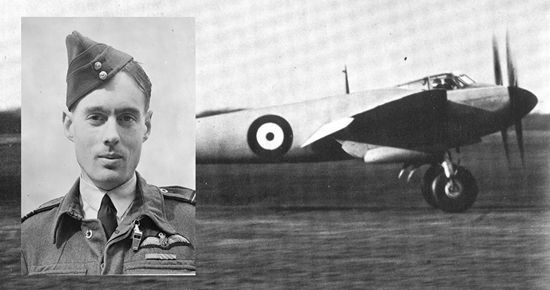

Eric James Brindley Nicolson / Hawker Hurricane. Photo Imperial War Museum. Eric James Brindley Nicolson VC DFC (29 April 1917 - 2 May 1945) joined the Royal Air Force No. 72 Squadron in 1937 and after completing his training he moved to No. 249 Squadron in 1940. Nicolson was 23 years old and a flight lieutenant when he was awarded the Victoria Cross. On 16 August 1940 near Southampton, Nicolson's Hawker Hurricane was fired on by a Messerschmitt Bf 110, injuring him in one eye and one foot. His engine was also damaged and the petrol tank set alight. As he struggled to leave the blazing machine he saw another Messerschmitt, and managing to get back into the bucket seat, pressed the firing button and continued firing until the enemy plane dived away to destruction. Not until then did he bail out, and he was able to open his parachute in time to land safely in a field. On his descent, he was fired on by members of the Home Guard, who ignored his cry of being a RAF pilot. As a Wing Commander, he was killed on 2 May 1945 when a RAF B-24 Liberator from No. 355 Squadron, in which he was flying as an observer, caught fire and crashed into the Bay of Bengal. His body was not recovered. He is commemorated on the Singapore Memorial. Nicolson was the only Battle of Britain pilot and the only pilot of RAF Fighter Command to be awarded the Victoria Cross during the Second World War.

Lloyd Allan Trigg /Consolidated Liberator Photo USAF / commons.wikimedia.org. New Zeelander Lloyd Allan Trigg VC DFC (5 May 1914 - 11 August 1943), of Houhora, New Zealand, joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) as a trainee pilot in June 1941. After attending training school in Canada, Trigg obtained his pilot's wings on 16 January 1942, and was commissioned as a Pilot Officer. After receiving further training in Lockheed Hudson aircraft he embarked for the UK in October 1942. Trigg was posted to West Africa in December 1942 and joined 200 Squadron RAF in January 1943. As a first pilot he took part in some 50 operational reconnaissance patrols, convoy escort flights and anti-submarine patrols. On 11 August 1943 Trigg undertook, as captain and pilot, a patrol in a Liberator although he had not previously made any operational sorties in that type of aircraft. After searching for 8 hours a surfaced U-boat was sighted. Flying Officer Trigg immediately prepared to attack. During the approach, the aircraft received many hits from the submarine's anti-aircraft guns and burst into flames, which quickly enveloped the tail. Trigg could have broken off the engagement and made a forced landing in the sea. There was no hesitation or doubt in his mind. He maintained his course in spite of the already precarious condition of his aircraft and executed a masterly attack. Skimming over the U-boat at less than 50 feet with anti-aircraft fire entering his opened bomb doors, Trigg dropped his bombs on and around the U-boat where they exploded with devastating effect. A short distance further on the Liberator dived into the sea. The U-boat sank within 20 minutes and some of her crew were picked up later in a rubber dinghy that had broken loose from the Liberator. Trigg's exploit stands out as an epic of grim determination and high courage. He was a posthumous recipient of the Victoria Cross,

Leslie Thomas Manser / Avro Manchester Photo commons.wikimedia.org. British bomber pilot Leslie Thomas Manser VC (11 May 1922 - 31 May 1942) was born in New Delhi, India during his father's employment as an engineer with the Post and Telegraph Department. He was accepted by the Royal Air Force in August 1940, and was commissioned as a Pilot Officer in May 1941. After a navigational course and final operational training at 14 OTU, RAF Cottesmore, he was posted to No. 50 Squadron (which was operating the Handley Page Hampden) at RAF Swinderby, Lincolnshire on 27 August. Two days after joining his squadron Manser experienced his first operation: as a second pilot, he took part in a bombing raid on Frankfurt. For the 1,000 bomber raid on Cologne on the night of 30 May 1942, Manser was captain and first pilot of Avro Manchester bomber 'D' for Dog. As he came over the target, his aircraft was caught in searchlights and although he bombed the target successfully from 7,000 ft (2,100 m) it was hit by flak. In an effort to escape the anti-aircraft fire he took violent evasive action, this reduced his altitude to only 1,000 ft (300 m) but he did not escape the flak until he was clear of the city. By this time the rear gunner was wounded, the front cabin full of smoke and the port engine overheating. Rather than abandon the aircraft and be captured, Manser tried to get the aircraft and crew to safety. The port engine then burst into flames, burning the wing and reducing airspeed to a dangerously low level. The crew made preparations to abandon the aircraft, by then barely controllable and with a crash inevitable. The aircraft was by now over Belgium, and Manser ordered the crew to bail out, but refused the offer of a parachute for himself. He remained at the controls and sacrificed himself in order to save his crew. As the crew parachuted down they saw the bomber crash in flames into a dyke at Bree, 13 mi (21 km) north east of Genk in Belgium. P/O Barnes was taken prisoner, but Sgt Baveystock, P/O Horsley, Sgt King, Sgt Mills and Sgt Naylor all evaded capture and made their way back to the UK. The testimonies of the five evaders were instrumental in the posthumous award of the VC.

De Havilland Mosquito/Group Captain L Chesire Photo commons.wikimedia.org. Group Captain Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire, Baron Cheshire VC, OM, DSO & Two Bars, DFC (7 September 1917 - 31 July 1992) was the highest decorated Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot during the Second World War. He received his commission as a pilot officer in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on 16 November 1937. Following the outbreak of war, Cheshire joined the RAF on 7 October 1939 with a permanent commission. He was sent for training at RAF Hullavington and was promoted to flying officer on 7 April 1940 and was posted that June to 102 Squadron, flying Armstrong Whitworth Whitley medium bombers. In November 1940, Cheshire was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for flying his badly damaged bomber back to base. In January 1941, Cheshire completed his tour of operations, but then volunteered immediately for a second tour. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in March 1941 and was promoted to the war substantive rank of flight lieutenant on 7 April. He was posted to No. 35 Squadron with the brand new Handley Page Halifax and completed his second tour early in 1942, by then a temporary squadron leader. On 30 September 1943 he was promoted wing commander at the legendary 617 "Dambusters" Squadron. While with 617 While with 617, Cheshire helped pioneer a new method of marking enemy targets for Bomber Command's 5 Group, flying in at a very low level in the face of strong defences, using first, the versatile de Havilland Mosquito, then a North American Mustang fighter. Cheshire was nearing the end of his fourth tour of duty in July 1944, having completed a total of 102 missions, when he was awarded the Victoria Cross. His citation remarked on the entirety of his operation career, noting: "In four years of fighting against the bitterest opposition he maintained a standard of outstanding personal achievement, his successful operations being the result of careful planning, brilliant execution and supreme contempt for danger - for example, on one occasion he flew his Mustang in slow 'figures of eight' above a target obscured by low cloud, to act as a bomb-aiming mark for his squadron. Cheshire displayed the courage and determination of an exceptional leader." It also gave special mention to a raid against Munich on 24/25 April 1944, in which he had marked a target while flying a Mosquito at low level against "withering fire".

Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde / Fairy Swordfish Photo Abbie Herron / commons.wikimedia.org. Lieutenant Commander Eugene Kingsmill Esmonde VC DSO, F/Lt, RAF, Lt-Cdr (A) RN (1 March 1909 - 12 February 1942) was a distinguished British pilot who was a posthumous recipient of the Victoria Cross (VC). Esmonde was commissioned into the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a pilot officer on probation on 28 December 1928.[2] During the early 1930s, Esmonde served first in the RAF, and then transferred to the Fleet Air Arm where he served in the Mediterranean when responsibility for naval aviation was returned to the Royal Navy. On 12 February 1942 off the coast of England, Esmonde led a detachment of six Fairey Swordfish in an attack on the German battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. All three had left Brest unopposed, and, with a strong escort of smaller craft, were entering the Straits of Dover when Esmonde received his orders. He waited as long as he felt he could for confirmation of his fighter escort, but eventually took off without it. One of the fighter squadrons (10 Supermarine Spitfires of No. 72 Squadron RAF) did rendezvous with Esmonde's squadron; the two squadrons were later attacked by enemy fighters of JG 2 and JG 26 as part of Operation Donnerkeil, the German air superiority plan for the mission. The subsequent fighting left all of the planes in Esmonde's squadron damaged, and caused them to become separated from their fighter escort. The torpedo bombers continued their attack, in spite of their damage and lack of fighter protection. There was heavy anti-aircraft fire from the German ships, and Esmonde's plane possibly sustained a direct hit from anti-aircraft fire that destroyed most of one of the port wings of his Swordfish biplane. Esmonde led his flight through a screen of the enemy destroyers and other small vessels protecting the battleships. He was still 2,700 metres from his target when he was hit by a Focke-Wulf Fw 190, resulting in his aircraft bursting into flames and crashing into the sea. The remaining aircraft continued the attack, but all were shot down by enemy fighters; only five of the 18 crew survived the action. The four surviving officers received the Distinguished Service Order, and the enlisted survivor was awarded the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. Esmonde was awarded the VC posthumously.

Rawdon Hume "Ron" Middleton / Short Stirling Photo en.wikipedia.org. Australian Rawdon Hume "Ron" Middleton VC (22 July 1916 - 29 November 1942) enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force on 14 October 1940, and trained as a pilot in the Empire Air Training Scheme. He undertook initial flying training at No. 5 Elementary Flying Training School (5 EFTS) Narromine NSW, and advanced training in Canada. In February 1942 he joined No. 149 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, flying as second pilot on Short Stirling bombers. By July of that year he was appointed as an aircraft captain, and flew his first raid as a pilot-in-command against Düsseldorf. On 28 November 1942, Middleton was captain of Stirling detailed to bomb the Fiat aircraft works at Turin. It was his twenty-ninth combat sortie, one short of the thirty required for completion of a 'tour' and mandatory rotation off combat operations. Middleton and his crew arrived above Turin after a difficult flight over the Alps. Over the target area Middleton had to make three low-level passes in order to positively identify the target; on the third, the aircraft was hit by heavy anti-aircraft fire which wounded both pilots and the wireless operator. Middleton suffered numerous grievous wounds, including shrapnel wounds to the arms, legs and body, having his right eye torn from its socket and his jaw shattered. He passed out briefly, and his second pilot, Flight Sergeant L.A. Hyder, who was also seriously wounded, managed to regain control of the plunging Stirling at 800 feet and drop the bombs, before receiving first aid from the other crew. Middleton regained consciousness in time to help recover control of his stricken bomber. Middleton was in great pain, was barely able to see, was losing blood from wounds all over his body, and could breathe only with difficulty. He must have known that his own chances of survival were slim, but he nonetheless determined to fly his crippled aircraft home, and return his crew to safety. After four hours of agony and having been further damaged by flak over France, Middleton reached the coast of England with five minutes of fuel reserves. At this point he turned the aircraft parallel to the coast and ordered his crew to bail out. Five of his crew did so and landed safely, but his front gunner and flight engineer remained with him to try to talk him into a forced landing on the coast, something he must have known would have risked extensive civilian casualties. He steered the aircraft out over the sea, off Dymchurch, and ordered the last two crew to bail out. They then too bailed out, but did not survive the night in the English Channel. Middleton stayed with the aircraft, which crashed into the Channel. His body was washed ashore on 1 February 1943. The Victoria Cross was awarded posthumously.

Leonard Henry Trent / Lockheed Ventura Photo Imperial War Museums commons.wikimedia.org. New Zeelander Leonard Henry Trent VC DFC (14 April 1915 - 19 May 1986) undertook Royal New Zealand Air Force flight training in Christchurch, gaining his wings in May 1938. A month later he sailed for Britain to join the Royal Air Force. In September 1939 Trent went to France as part of No. 15 Squadron RAF, flying Fairey Battles on high-level photo-reconnaissance missions over enemy territory. The squadron returned to England in December to convert to the Bristol Blenheim IV. Trent flew numerous combat missions after Germany invaded the Low Countries and France in May 1940. In July 1940 he received the DFC for his outstanding contribution to the Battle of France. Trent was also tasked withmany difficult raids on targets in the Low Countries during the late 1942 and early 1943. On 3 May 1943 the squadron was ordered on a Ramrod diversionary bombing attack on the power station in Amsterdam. No.s 118 Sqn, 167 and 504 Squadrons of the Coltishall Wing were to escort the Venturas, and were to be met by further squadrons of No. 11 Group, Fighter Command over the Dutch coast. The Venturas were to cross the coast at sea level so as not to alert German radar, then climb. Unfortunately the 11 Gp Mk IXs flying ahead of the Venturas arrived early and crossed the coast high, being anxious to gain a height advantage. They ran low on fuel before the Venturas arrived and had to leave. The Luftwaffe scrambled some 70 fighters in four formations, with Focke-Wulf Fw 190s to deal with the escort and Messerschmitt Bf 109s the bombers. The escort Wing Leader, Wg Cdr Blatchford, vainly attempted to recall the bombers but they were soon hemmed in by fighters. Under constant attack by II Gruppe, Jagdgeschwader 1, 487 Squadron continued on to its target, the few surviving aircraft completing bombing runs before being shot down. The Squadron was virtually wiped out. Trent shot down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 with the forward machine guns of his plane. Immediately afterwards, his own Ventura was hit, went into a spin and broke up. Trent and his navigator were thrown clear at 7,000 feet and became prisoners. Trent, whose leadership was instrumental in ensuring the bombing run was completed, was awarded the Victoria Cross.

James Allen Ward / Vickers Wellington Photo commons.wikimedia.org. James Allen Ward VC (14 June 1919 - 15 September 1941enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) on 2 July 1940. He trained as a pilot at Taieri and Wigram. Ward was stationed at 20 OTU Lossiemouth, in Scotland. Ward was a 22-year-old sergeant pilot with No. 75 (NZ) Squadron when he carried out the action for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC). He was co-pilot on a Vickers Wellington bomber flying out of RAF Feltwell in Norfolk, United Kingdom. On 7 July 1941 after an attack on Münster, Germany, the Wellington (AA-R) in which Sergeant Ward was second pilot was attacked by a German Bf 110 night fighter. The attack opened a fuel tank in the starboard wing and caused a fire at the rear of the starboard engine. The skipper of the aircraft told him to try to put out the fire. Sergeant Ward crawled out through the narrow astrodome (used for celestial navigation) on the end of a rope initially reported as being taken from the aircraft's emergency dinghy, but actually from an engine cover. He kicked or tore holes in the aircraft's fabric with a fire axe to give himself hand- and foot-holes. By this means he reached the engine and attempted to smother the flames with a canvas cover. Although the fuel continued to leak, with the fire out the plane was now safe. His crawl back over the wing, in which he had previously torn holes, was more dangerous than the outward journey but he managed with the help of the aircraft's navigator. Instead of the crew having to bail out, the aircraft made an emergency landing at Newmarket, United Kingdom.

Part four, the Avro Lancaster to follow.

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.

Copyright © 2024 Pilot's Post PTY Ltd

The information, views and opinions by the authors contributing to Pilot’s Post are not necessarily those of the editor or other writers at Pilot’s Post.